Estimating the risk of failure

In 2018 Ian Haley was among a group of 312 patients, who sued Depuy in the English High Court because they had an adverse reaction to metallic debris (ARMD) from the hip’s metallic bearing surfaces. So, they claimed that the Pinnacle Hips with a metal on metal (MoM) bearing were legally defective.

Their claim was based on Part 1 of the Consumer Protect Act implementing the European Product Liability Directive in British Law.

In Article 6 the Directive says:-

A product is defective when it does not provide the safety which a person is entitled to expect, taking all circumstances into account,

Article 6 (1) of the European Product Liability Directive

The patients’ first claim against Depuy, alleging that the defect was the ‘production of metal wear particles from the bearing surfaces’, is discussed in my previous post.

So now we will turn our attention to the patients’ secondary claim that:-

…”the Pinnacle Ultamet prosthesis had “an abnormal potential for damage, compared with existing established non-MoM total hip replacement prostheses and/or that a large head MoM articulation had an abnormal potential for damage compared to alternative bearing surfaces within the Pinnacle modular system”

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 136

The Statistical Evidence

The Judge – Mrs Justice Andrews – established a two stage test for the claimants to satisfy in order to obtain compensation:-

- Firstly, they must show that the risk of revision surgery – to repair or replace their hip – within 10 years was significantly increased by the use of a Pinnacle MoM hip, compared with alternative products already accepted in the market place in 2002.

- Secondly, individual patients must show that, on the balance of probabilities their revision surgery was the result of the increased risk, associated with the development of ARMD

Discussing how the first test could be satisfied, Mrs Justice Andrews observed that:-

If it were to be established that the incidence of early failure of Pinnacle Ultamet hips by reason of ARMD was more than double the general incidence of early failure of comparator hip prostheses, then of course the claimant would discharge the burden of proving causation. However, I am not persuaded that this is the only way in which causation could be established, or that “more than double the risk” should be adopted as a bright-line test in a case such as this,

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 186

But satisfying the first test would require information about the experience of patients who had received different types of hip joint – manufactured by Depuy and their competitors. In particular how many of them had needed revision surgery to repair or replace their hip within 10 years?

Finding the data to assess the risk

During the process of discovery, Depuy could be asked to reveal the information they had, but their competitors were under no obligation to tell them what they knew about the durability and performance of their alternative products.

So the claimants had to rely on information held in independent ‘joint registries’ or databases compiled by various government agencies and academic organisations, including:-

- The Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry (SHAR)

- UK’s National Joint Registry (NJR) for NHS hospitals (excluding Scotland)

As the name implies, registries compile a list of patients who have received hip implants and record their post-operative experience – for as long as they are being monitored by their hospital or surgeon.

The Swedish Registry, SHAR, started in 1979 was designed to record the post operative experience of patients who received different treatments, monitoring the performance of hospitals and their surgical teams. Their reports comparing the ‘success rate’ of different treatments encourage the sharing of best practice, by highlighting the lessons to be learnt and problems to be solved in developing new treatments and medical devices.

Justice Andrews observed that:-

…… the SHAR data were the only long-term data available at the time when the Pinnacle Ultamet was introduced, and the data in the 2000 SHAR report informed the views of orthopaedic surgeons and NICE as to the likely survivorship of the alternative MoP (Metal on Plastic) prostheses,

Pinnacle Judgement Paragraph 321

As the UK’s registry – the NJR – only started collecting data in 2003, after the Pinnacle Hip was introduced, their data could not influence the public’s expectations of safety for the Pinnacle Hip. But the NJR data may give us some insight into the actual performance of the Pinnacle Hips fitted after 2003.

As Depuy pointed out the majority of patients receiving an artificial hip hope to survive for more than 10 years, and the ‘design life’ of their hips is typically 20 – 25 years. But, the Product Liability Directive only applies to claims that are submitted within 10 years of the particular product being supplied. So, the Court considered the most appropriate measure of joint performance to be the risk of revision surgery, or Case Revision Rate (CRR), within 10 years.

The reliability of any analysis is limited by the quality of the data supplied by the hospitals, and the way that the data has been structured. So, for example:-

- Later SHAR Reports presented data for Depuy’s Pinnacle Hip, but grouped all versions together, mixing the results for MoM and MoP versions.

- The NJR reports, based on information supplied by the NHS hospitals, did identify the type of Pinnacle hip – MoM or MoP – used. But Depuy raised concerns about the quality of the NJR data because not all patients were uniquely identified, and the data was incomplete.

Moving goal posts

The actual performance – or 10 year case revision rate – of hips implanted in 2002 could not be known until 2012. But the level of safety the public were entitled to expect when the Pinnacle Hip was introduced, in 2002, was based on the expected performance of competing products already accepted in the market place.

The SHAR Reports published in 2000 and 2002 provided the most reliable information about those alternative products – tracking the experience of patients in each annual cohort. But, as patients who received their hips less than 10 years ago, were ‘still at risk’ and might need revision surgery in the future, their 10 year Case Revision Rates could only be estimated based on the existing data.

The expert’s analysis also had to recognise the improvements in surgical techniques, materials and product design that may have contributed to progressive improvements in the Case Revision Rate – raising the public’s expectations of safety over the previous 10 years, from 1990 onward.

In the 1990’s the majority of hip implants:-

- Were performed on older patients, with a less active life style, usually as the the result of osteoarthritis.

- Were a ‘cemented design’, with the stem glued into to the top of the femur using a quick drying cement

Unfortunately the cemented metal on plastic (MoP) joints developed in the 1980’s and 1990’s were not recommended for younger more active patients, because they were prone to aseptic loosening of the stem as the cement degraded over time, as well as wear of the plastic components, with an increasing risk of revision surgery after 10-15 years.

To address these known issues, the Pinnacle range offered by Depuy:-

- Was an uncemented design, relying on the growth on new bone fused with the surface of the stem to hold the implant in place

- Offered as an option, a metal on metal (MoM) bearing which would be hard wearing and hopefully more durable in younger more active patients.

Depuy and other manufacturers had previously started to introduce ‘uncemented’ hips with metal on plastic (MoP) or metal on ceramic (MoC) bearings during the 1990’s. But most of these newer designs had not been in use for a full 10 years when the SHAR 2000 and 2002 reports were published.

To improve the performance of metal on plastic (MoP) hips, material scientists also developed new plastic materials that cross-linked their polymer chains to reduce wear rates. The introduction of these cross linked (XPLE) and hyper cross linked materials (HXPLE) after 2005 reduced the risk of revision surgery due to osteolysis – a reaction to plastic wear particles from MoP joints.

So, in her judgement Justice Andrews was careful to ensure that the statistics used fairly reflected improvements in product design and surgical techniques between 1990 and 2018, and that comparisons were made on a like for like basis – when possible.

Measures of Risk

Depuy and the claimants both instructed statistical experts to analyse the available data and prepare expert reports for the Court, explaining the risk of revision surgery with different types of hip joint.

To help the Judge understand their findings, their Experts Joint Report identified what they agreed about and explained the reasons for any disagreement.

Their analysis had to allow for patients who had:-

- Survived for 10 years without requiring revision surgery.

- Required revision surgery within 10 years

- Had their operation less than 10 years ago, and were still at risk

- Died within 10 years without requiring revision surgery

- Had dropped out of the follow-up program with an unknown status

The Case Revision Rate (CRR), is the probability that a joint will need need repair or replacement – assuming the patient is still alive – within the 10 year period.

Patients were grouped into cohorts who had their operation at the same time, for example the 2002 cohort, allowing the effects of changes in surgical techniques etc to be assessed. But, we can only know the actual case revision rate if we are patient enough to wait for 10 years!

So, for joints that have been fitted less than 10 years ago, the Case Revision Rates must be estimated based on their performance to date with some adjustments made for failures that are expected in the remaining time.

The experts also tried to isolate the effect of different variables on the Case Revision Rate (CRR), including:-

- The performance of different hospitals and surgeons

- The patient’s age, sex and weight when the hip was implanted.

- Long term trends that may indicate improvements in surgical techniques

- The materials used in the joint, metal on metal or metal on plastic

- If recorded the reasons for performing revision surgery

As estimates based on statistical data are always a bit uncertain – they provided their best guess – or point values – and the margin of error or confidence limits around that value for each estimate of the Case Revision Rate (CRR).

The Confidence Limits give the range of credible values, and indicate how repeatable the results may be if the analysis was repeated using a different sample of data. In general, estimates based on a small sample of data will be less reliable – so they will have a greater range of credible values.

When making comparisons, for example between different hip designs, we may see an apparent difference between their estimated CRR values – but also find that the range of credible values overlap – so we can’t be confident that the apparent difference is significant or meaningful.

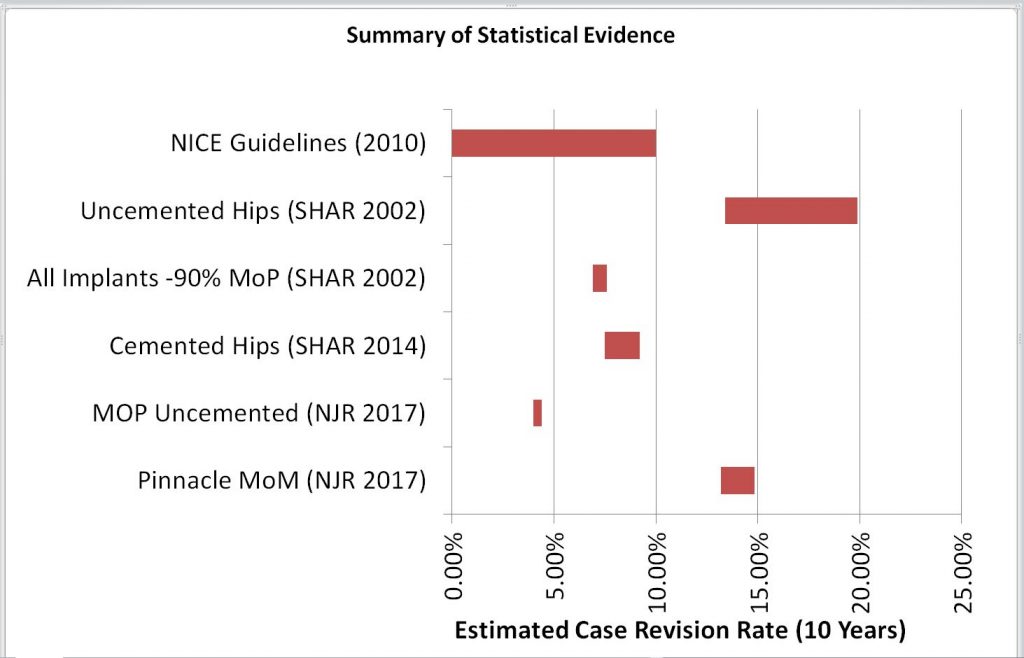

So, the Judge was presented with estimates of the Case Revision Rate for different types of hip joint, based on the SHAR and NJR reports – as shown below:-

| Data Set | Min | Point | Max |

| Pinnacle MoM (NJR 2017) | 13.2% | 14.0% | 14.8% |

| MOP Uncemented (NJR 2017) | 4.0% | 4.2% | 4.4% |

| Cemented Hips (SHAR 2014) | 7.5% | 8.3% | 9.2% |

| All Implants -90% MoP (SHAR 2002) | 6.9% | 7.2% | 7.6% |

| Uncemented Hips (SHAR 2002) | 13.4% | 16.7% | 19.9% |

| NICE Guidelines (2010) | 10.0% |

In 2000 the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) had published guidance to help surgeons select hip implants for patients, based on the SHAR 2000 Report. The guidance said:-

Using the most recent available evidence of clinical effectiveness, the best prostheses (using long term viability as the determinant) demonstrate a revision rate (the rate at which they need to be replaced) of 10% or less at 10 years. This should be regarded as the current “benchmark” in the selection of prostheses for primary total hip replacement.

Pinnacle Judgement, Paragraph 457 quoting NICE Guidance

Although the NICE guidance was based on the SHAR 2000 report showing the rate of revisions for ‘all hips’, it appeared to ignore the higher revision rates for ‘uncemented hips’ shown in that report.

The SHAR Reports were considered to be the most reliable source of data, but were based on the experience in Sweden, where the surgical techniques and patient demographics may be be different from the UK

Although the 2014 SHAR Report presented data for different brands and models of hip joint, including the modular Pinnacle range, it did not separate the alternative bearing materials – MoP or MoM – within the Pinnacle range. So the claimants relied instead on data from the 2017 NJR report to calculate the actual case revision rate for the Pinnacle Hip with a metal on metal (MoM) bearings.

The UK’s National Joint Registry (NJR) started collecting data in 2003, and their reports are based on the data from NHS hospitals in the UK, excluding Scotland. Although Justice Andrews was concerned about the quality and reliability of the NJR’s data, it did separate the data for the MoP and MoM versions of the Pinnacle Hip.

After both experts had been questioned and cross examined, in her judgement Justice Andrews diligently analysed their evidence and the quality of the raw data they had used.

Reaching a conclusion

Under the European Product Liability Directive, to win compensation the claimants must prove that the product was defective, and that the defect caused their injury. Although as Justice Andrews explained, the description of the defect must also be directly related to an increased or unacceptable risk of harm, so that the product does not provide the level of safety the public are entitled to expect.

When some abnormality, or non-conformity, in the product supplied introduces a new or significantly increased risk, the claimants may argue that:-

- ‘But for the abnormality’ the product would have achieved an acceptable level of safety, and their loss would not have occurred

But when, as in this case, the harm is the result of a ‘known risk’ and attributed to the normal characteristics of the product it becomes more difficult to prove that the product did not provide the level of safety they were entitled to expect.

To succeed the claimants would need to show that the probability that patient would require revision surgery was significantly increased by the choice of a Pinnacle MoM hip – rather than an alternative metal on plastic design.

So, the claimants argued that, based on the NJR 2017 Report, the risk of revision surgery within 10 years:-

- For an alternative uncemented metal on plastic (MoP) hip was about 5%,

- For the Pinnacle MoM hip, was about 14%

But Depuy argued that the NJR data was not reliable, pointing instead to the NICE guidelines published in 2000, and the SHAR Reports published in 2000, 2002 and 2014, because:-

- The SHAR 2002 Report suggested that 10 year Case Revision Rate all hip joints was in the range 6.9 – 7.6%

- According to SHAR, Case Revision rates were higher for younger more active patients.

- The NICE guidelines published in 2000, based on the SHAR 2000 report recognised that “….the best prostheses demonstrate a revision rate of 10% or less at 10 years. This should be regarded as the current “benchmark” …”

So, Mrs Justice Andrews had to decide if the Pinnacle MoM hip was defective, or provided the level of safety the public were entitled to expect in a product of that type. Her reasoning, explained in my next post, provides an interesting precedent that may be followed in the future.

To learn more…

To learn more about Product Liability and risk management please contact Phil Stunell or subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates.

Leave a Reply